If you’ve ever seen the Save the Cat! Beat Sheet you probably asked, “what the hell is the Debate beat?” According to the creator himself, this is one of the most frequent questions he got.

The Save the Cat! Beat Sheet is a renowned storytelling tool developed by the late screenwriter Blake Snyder, designed to help writers create engaging and well-structured narratives. Derived from Snyder’s book “Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need,” the beat sheet outlines key plot points and emotional beats essential for a successful screenplay.

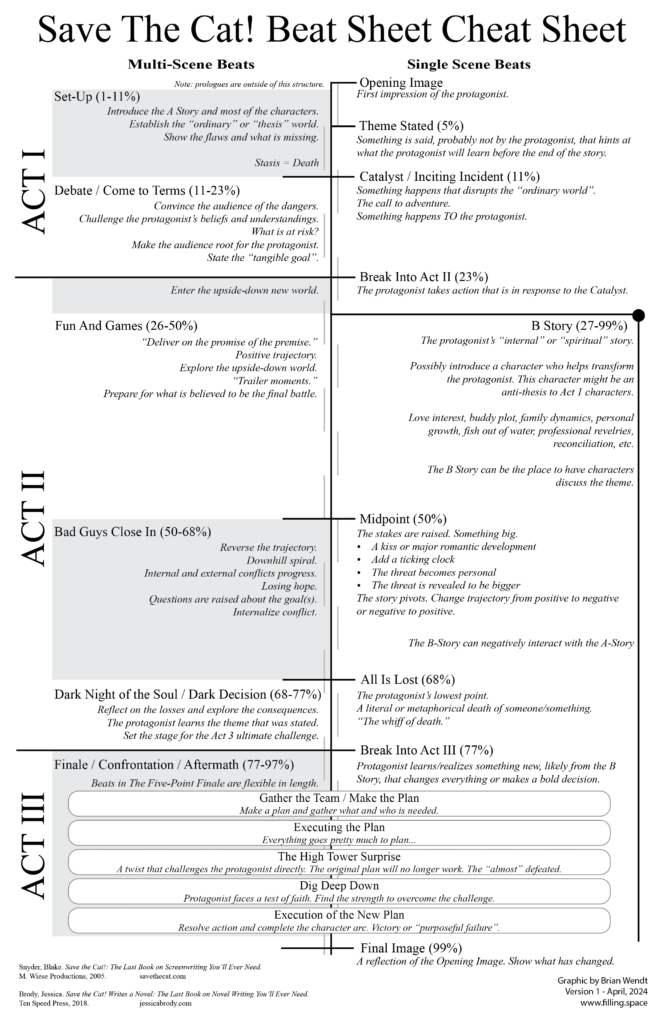

If you haven’t already, download my Save the Cat! Beat Sheet Cheat Sheet [PDF]. It’s free and incredibly helpful for anyone learning this tool.

The Beat Sheet is divided into specific sections, each representing a crucial turning point in the protagonist’s journey, including the opening image, catalyst, debate, and finale, among others. The debate beat is the 5th beat and starts at about the 10% mark, immediately after the inciting incident, and ends around the 20% mark when the protagonist takes actions thus “breaking into act 2”. So who is debating about what?

The debate beat is tricky because it is frequently poorly explained. Even in Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need, I think Blake doesn’t sufficiently clarify the purpose of the debate which is why so many new storytellers (screenwriting or otherwise) struggle with it. Here are a few tips for nailing your debate.

The Debate “Beat”

Because the debate beat is frequently multiple scenes, I generally consider this a section like the Setup, Fun and Games, Bad Guys Close In, Dark Night of the Soul, and Finale. The multi-scene beats are described in Snyder’s beat sheet as page ranges instead of page numbers he expects the beat to occur on. In my cheat sheet, I differentiate single-scene beats from multi-scene beats (sections) to help you understand the difference.

What is Being Debated?

Traditionally, the description of this beat goes something along the lines of “the protagonist must decide if they will take action in response to the catalyst“. I think this confuses the matter. In many stories, the hero doesn’t have much choice on what action they’ll take. Bilbo Baggins had a choice and he had a personal debate with himself about whether he’d accept the Call To Action or not. This sort of catalyst is fairly easy to understand for many storytellers and is a common dynamic in stories.

But some catalysts are thrust upon the protagonist. In Saving Private Ryan, Captain Miller is ordered to go on a very dangerous mission to save the 4th and last Ryan son. Captain Miller can’t really say no and he doesn’t earnestly debate saying no to a direct order. He debates how to approach taking action. His debate leads him to take charge of the group instead of passively being the leader only in name. Captain Miller does this by giving an emotionally vulnerable speech that rallies his men to the cause.

Who is Being Debated?

That common description of the debate beat (“the protagonist must decide if they will take action in response to the catalyst“) puts the focus on the character. Your job as a storyteller is to create a compelling narrative, one that speaks to the audience.

So who is actually debating in this beat? You and the audience. That is one of the most important things you need to know to write your debate beat. The debate is less about the characters and far more about the audience. This section needs to convince the viewer/reader that the course of action the protagonist will set out on in the next beat is a valid direction. This section has to sell the audience on what is at stake and why it matters.

Going back to Saving Private Ryan, the speech that moves the story into Act 2 (the “Break Into II” beat) is a monologue by to protagonist that convinces the viewer that risking their lives to save one person is a worthwhile thing to do, not just something to do because they were ordered to do so. His speech happens to also convince the group of soldiers he’s taking with him.

“In Conclusion”

Convince your audience what the stakes are so that the action is gripping. Not just in the debate beat, but throughout your entire story. The debate section is where you lay it all out but in every beat, you must remind the audience by indulging, annoying, murdering, or even intentionally abandoning the things important to the protagonist. Make your audience care about the stakes and then keep the stakes ever in the audience’s front of mind.